Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HHC) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the United States, affecting approximately 1.5 million persons. HHC is characterized by increased iron absorption in the gastrointestinal tract that may cause lifelong excessive iron absorption and accumulation and serious health effects including arthritis, cirrhosis, diabetes, impotence, myocardial infarction, and death.

Deposition of iron within tissues causes inflammation and subsequent fibrosis and destruction of major organs leading to organ failure and chronic disease. HHC often goes undetected and untreated until symptoms of permanent organ damage become apparent.

HHC was first recognized more than a century ago as an iron overload condition presenting as a clinical triad – type 2 diabetes mellitus, skin bronzing, and cirrhosis of the liver. Several causes for iron overload exist, the primary ones being genetically based. Secondary iron overload may be the result of excessive transfusion therapy, poorly responding anemia being treated with iron supplementation, or chronic liver disease due to alcohol abuse.

Persons with normal hemoglobin levels and iron stores absorb just enough iron to meet their daily needs and balance losses (1mg per day). No internal mechanism exists for excreting excess iron absorbed from the diet. The amount of iron absorbed is influenced by the amount of iron stored in the body, the rate and effectiveness of red blood cell creation, the amount and form of iron in the diet, and the presence of iron absorption enhancers and inhibitors in the diet. However, patients with HHC continue to absorb high amounts of dietary iron even when their bodies have enough or too much iron.

HHC patients can chronically absorb a small excess of iron each day, resulting in iron stores 10 times the normal amount by the time they are middle-aged. The body is unable to adequately chelate and store this amount of iron. Therefore, unbound iron accumulates and generates free radicals, leading to cellular injury of the liver and other organs.

Ethnic Factors

HHC is commonly underdiagnosed in white patients. In other ethnic groups, such as African Americans and Hispanics, it may not even be considered despite the presentation of signs and symptoms strongly suggestive of iron overload. The prevalence of iron overload among Hispanic persons is estimated to be as high as 5 in 1000 persons.

HHC, an autosomal recessive disorder previously considered to be rare, is now known to be the most prevalent genetic disease in individuals of northern European descent. The hemochromatosis gene is responsible for most cases of HHC. The prevalence of the homozygous genotype is estimated to be 1 in 250 persons; the prevalence of the heterozygous genotype is approximately 1 in 8 persons.

Evidence suggests that primary iron overload may be common in African Americans. Hepatic iron excess was observed in 1.5% of African Americans during a recent autopsy series and in 10.4% of African Americans who underwent liver biopsy during medical care delivery. In a large nutrition survey among the general African American population aged 3 to 45 years, hyperferritinemia consistent with iron overload was more common among African Americans than whites.

Signs and symptoms

The first symptoms associated with iron overload are often nonspecific and the disorder may not be considered in the differential diagnosis. Consequently, the underlying cause may not be recognized and treated and organ damage may continue. At least 50% of men and 25% of women with both genes for HHC are likely to develop potentially life-threatening disease complications, especially in countries where there is high dietary intake of iron.

The clinical manifestations of HHC usually do not appear until a person is aged 40 to 60 years, when sufficient iron has accumulated to cause organ damage. Some persons have clinical manifestations by 20 years of age, but others with both genes for the disease may never have clinical signs. An estimated 67% to 94% of men and 41% of women with HHC show signs and symptoms of the disease after 40 years of age.

The use of supplementary iron and vitamin C (which increases iron absorption) may lead to earlier laboratory abnormalities and iron deposition. Conversely, blood donation, physiologic blood loss (through menstruation and pregnancy), and pathologic blood loss (for example, through peptic ulceration or inflammatory bowel disease) may decrease the amount of iron stored in the liver. However, the belief that premenopausal women cannot develop symptomatic or even life-threatening HHC is a misconception.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus develops in about 65% of patients and is more commonly a complication in patients with a positive family history for diabetes. Hypogonadism is common in both sexes and can lead to loss of libido, impotence, amenorrhea, testicular atrophy, and loss of body hair.

Arthropathy is present in up to 50% of symptomatic patients. Occasionally, acute episodes of an inflammatory arthritis occur; some of these episodes are caused by deposits of calcium.

Diagnosis

Liver biopsy continues to be the gold standard for diagnosis and staging of HHC because it can detect the level of iron overload and identify hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis. Many specialists prefer liver biopsy to quantitative phlebotomy, particularly when clinical or laboratory evidence of hepatic involvement is present. In patients younger than 40 years who have an serum ferritin concentration of less than 750 ng/mL and normal liver enzyme levels, phlebotomy therapy can be started without a liver biopsy. In all other cases, biopsy remains essential for diagnosis and optimal management.

Diagnosis of HHC is commonly delayed until clinical manifestations have appeared and irreparable organ damage has occurred. Therefore, basic and continuing medical education about the disease is urgently needed. Simple screening tests, such as serum transferrin saturation and ferritin concentrations, can be helpful in discovering asymptomatic patients with iron overload.

Prognosis

The causes of death in untreated patients include cardiac failure (30%), liver failure or portal hypertension (25%), and hepatocellular carcinoma (30%). The degree of iron overload at the time of diagnosis, as well as organ dysfunction, have prognostic implications. The 5-year survival rate increases with treatment from 33% to 89%. However, discovering HHC prior to the onset of tissue or organ damage is very important. When HHC is found early and properly managed, long-term prognosis, including life expectancy, should not differ from that of persons without the disorder.

Performing iron studies on routine screening chemistry panels has become more commonplace as demonstrated by a study of 40 patients with newly diagnosed HHC prospectively referred to a tertiary university-based hepatology clinic. Clinical information, serum and liver iron studies, liver histology, and phlebotomy requirements were evaluated to see what features were most helpful in making the diagnosis.

The study documented that 83% of patients came to the attention of the medical staff as a result of routine blood screening. Of these patients, 73% were asymptomatic and 78% had normal physical examinations. Only 3 patients had cirrhosis from HHC alone, 2 patients were diabetic, and 2 patients had increased skin pigmentation. With the use of iron screening studies on routine serum chemistry panels, patients with HHC can be identified and subsequently treated before symptoms or organ damage occurs.

Signs, symptoms & indicators of Hemochromatosis (Iron overload)

(Very) low sperm count

(Severe) abdominal discomfort

Major fatigue for over 12/major fatigue for over 3/minor fatigue for over 3 months

Constant fatigue

Fatigue on light exertion

Light/minimal body hair

(Severe) pain under right side of ribs

Irritability

Backward-curving fingernails

Joint pain/swelling/stiffness

Darker/redder skin color

Excessive skin pigmentation (bronzing) is present in more than 90% of symptomatic patients at the time of diagnosis. Deposition of iron within the skin causes inflammation and enhances melanin production by melanocytes. Patients usually notice a generalized increased pigmentation and occasionally notice that they tan very easily. This is due to ultraviolet light exposure and iron acting synergistically to induce skin pigmentation. Fair-skinned persons, who usually tan poorly, may never develop hyperpigmentation despite large iron burdens. Ethnically dark-complexioned patients (for example, people of Mediterranean descent) can develop a striking almond-colored hue. With particularly heavy iron overload, visible iron deposits sometimes appear in the skin as a grayish discoloration.

Conditions that suggest Hemochromatosis (Iron overload)

Increased Risk of Stroke

According to a study published in Neurology, high iron levels in stroke patients may prompt more severe neurological symptoms and possibly increase brain damage. Elevations of iron may intensify post-stroke neurological problems such as increased weakness, speech and orientation difficulties, and decreased levels of consciousness. Stroke patients with high ferritin concentrations may also have larger areas of the brain damaged due to stroke. High body iron stores may increase free radical production in brain cells, thus prompting stroke progression.

Congestive Heart Failure

Congestive heart failure occurs in about 7% of symptomatic patients with hemochromatosis. If untreated, patients may develop an acute onset of severe congestive heart failure with rapid progression to death.

Arrhythmias/Dysrhythmias

Cardiac arrhythmia occurs in about 7% of symptomatic hemochromatosis patients.

Counter Indicators

Hypogonadism, Male

The disease may lead to the development of testicular atrophy, and occurs 5 times more frequently in men than women. Aside from diabetes mellitus, testicular atrophy is probably the most common endocrine manifestation of the disease; this is secondary to iron deposition in and dysfunction of the pituitary.

Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is usually caused by many years of alcohol abuse, but can also be caused by excess iron in the blood.

Cirrhosis of the Liver

Cirrhosis is the most common severe consequence of hemochromatosis.

Diabetes Type II

Iron deposits in the pancreas decrease insulin production which can lead to insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Hemochromatosis is also called bronze diabetes because those sufferers with diabetes can express a bronze-colored tint to their skin.

Patients with hemochromatosis can also be diagnosed with liver disease, diabetes, heart disease and arthritis without the physician realizing that these diseases are the result of iron-overload. Thus, the hemochromatosis might itself go undiagnosed and untreated.

Increased Risk of Liver Cancer

Once a person’s liver iron concentration reaches 400 mmol/gm (dry weight), cirrhosis is common and the risk of liver cancer and death is increased.

Increased Risk of Coronary Disease / Heart Attack

Male carriers of the common hemochromatosis gene mutation are at 2-fold risk of a first heart attack compared with noncarriers. Some 10% to 20% of the population carry at least one gene for hemochromatosis. Full-blown hemochromatosis affects about 0.5% and gene carriers usually do not know that they are at increased risk. They have almost no increase in iron stores over those without the mutation [Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association September 21, 1999;100].

Giving blood is the best way to lower iron stores, but a more recent study found no protective effect against heart attack among men who donated blood regularly. [Circulation January 2, 2001]

Having hemochromatosis

Counter Indicators

Absence of hemochromatosis

Risk factors for Hemochromatosis (Iron overload)

Alcohol-related Problems

Use of alcohol and other hepatotoxic drugs lowers the ability of the liver to safely store iron and may accelerate the development of the liver changes seen with hemochromatosis.

Elevated ferritin levels

High serum iron

(Very) low TIBC

While low TIBC is commonly explained by the presence of hemochromatosis, it can also be caused by hypoproteinemia from malnutrition, anemia with infection and chronic disease, and nephrosis.

Elevated liver enzymes

A common early sign of progressive iron overload is symptom-free elevation of liver enzymes, which can be accompanied by recurrent right-sided abdominal pain and liver enlargement. Liver disease, which is present in as many as 95% of patients with iron overload, is the most common complication.

Counter Indicators

Normal/elevated TIBC

While low TIBC is commonly explained by the presence of hemochromatosis, it can also be caused by hypoproteinemia from malnutrition, anemia with infection and chronic disease, and nephrosis.

(Very) low serum iron or normal serum iron

Birth Control Pill / Contraceptive Issues

Premenopausal women using oral contraceptives may have a decreased need for supplemental iron, as the use of OCs can increase iron stores. Iron testing may be appropriate in long term users.

Hepatitis

There have been reports that people with Hepatitis C have an increased risk of elevated iron levels. As such, it would be wise to run a serum ferritin test on anyone with Hepatitis C.

History of hemochromatosis

History of gout

Hemochromatosis (Iron overload) can lead to

Recommendations for Hemochromatosis (Iron overload)

Manganese

Manganese can protect against the free radical damage from excess iron. [Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 1992; 13: pp.115-20]

IP6 - Inositol Hexaphosphate

Supplemental IP6 may slow down the amount of iron being absorbed from the digestive tract, but only specially formulated drugs or blood loss can remove iron from the body.

Bloodletting / Phlebotomy

Once a diagnosis of HHC is confirmed, the excess iron should be removed and family members should be screened for the disorder. Iron overload is treated with successive phlebotomies in patients with or without clinical manifestations. The total amount of blood that must be removed to produce iron deficiency provides an estimate of total body iron load.

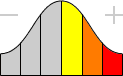

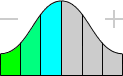

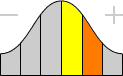

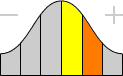

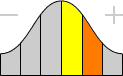

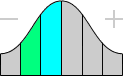

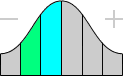

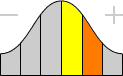

Key

| Weak or unproven link |

| Strong or generally accepted link |

| Proven definite or direct link |

| Strongly counter-indicative |

| Very strongly or absolutely counter-indicative |

| May do some good |

| Highly recommended |

| Avoid absolutely |

Glossary

Hemochromatosis

A rare disease in which iron deposits build up throughout the body. Enlarged liver, skin discoloration, diabetes mellitus, and heart failure may occur.

Iron

An essential mineral. Prevents anemia: as a constituent of hemoglobin, transports oxygen throughout the body. Virtually all of the oxygen used by cells in the life process are brought to the cells by the hemoglobin of red blood cells. Iron is a small but most vital, component of the hemoglobin in 20,000 billion red blood cells, of which 115 million are formed every minute. Heme iron (from meat) is absorbed 10 times more readily than the ferrous or ferric form.

Gastrointestinal

Pertaining to the stomach, small and large intestines, colon, rectum, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder.

Arthritis

Inflammation of a joint, usually accompanied by pain, swelling, and stiffness, and resulting from infection, trauma, degenerative changes, metabolic disturbances, or other causes. It occurs in various forms, such as bacterial arthritis, osteoarthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis, the most common form, is characterized by a gradual loss of cartilage and often an overgrowth of bone at the joints.

Cirrhosis

A long-term disease in which the liver becomes covered with fiber-like tissue. This causes the liver tissue to break down and become filled with fat. All functions of the liver then decrease, including the production of glucose, processing drugs and alcohol, and vitamin absorption. Stomach and bowel function, and the making of hormones are also affected.

Diabetes Mellitus

A disease with increased blood glucose levels due to lack or ineffectiveness of insulin. Diabetes is found in two forms; insulin-dependent diabetes (juvenile-onset) and non-insulin-dependent (adult-onset). Symptoms include increased thirst; increased urination; weight loss in spite of increased appetite; fatigue; nausea; vomiting; frequent infections including bladder, vaginal, and skin; blurred vision; impotence in men; bad breath; cessation of menses; diminished skin fullness. Other symptoms include bleeding gums; ear noise/buzzing; diarrhea; depression; confusion.

Chronic

Usually Chronic illness: Illness extending over a long period of time.

Anemia

A condition resulting from an unusually low number of red blood cells or too little hemoglobin in the red blood cells. The most common type is iron-deficiency anemia in which the red blood cells are reduced in size and number, and hemoglobin levels are low. Clinical symptoms include shortness of breath, lethargy and heart palpitations.

Hemoglobin

The oxygen-carrying protein of the blood found in red blood cells.

Milligram

(mg): 1/1,000 of a gram by weight.

Red Blood Cell

Any of the hemoglobin-containing cells that carry oxygen to the tissues and are responsible for the red color of blood.

Free Radical

A free radical is an atom or group of atoms that has at least one unpaired electron. Because another element can easily pick up this free electron and cause a chemical reaction, these free radicals can effect dramatic and destructive changes in the body. Free radicals are activated in heated and rancid oils and by radiation in the atmosphere, among other things.

Biopsy

Excision of tissue from a living being for diagnosis.

Vitamin C

Also known as ascorbic acid, Vitamin C is a water-soluble antioxidant vitamin essential to the body's health. When bound to other nutrients, for example calcium, it would be referred to as "calcium ascorbate". As an antioxidant, it inhibits the formation of nitrosamines (a suspected carcinogen). Vitamin C is important for maintenance of bones, teeth, collagen and blood vessels (capillaries), enhances iron absorption and red blood cell formation, helps in the utilization of carbohydrates and synthesis of fats and proteins, aids in fighting bacterial infections, and interacts with other nutrients. It is present in citrus fruits, tomatoes, berries, potatoes and fresh, green leafy vegetables.

Ulcer

Lesion on the skin or mucous membrane.

Premenopause

The period when women of childbearing age experience relatively normal reproductive function (including regular periods).

Acute

An illness or symptom of sudden onset, which generally has a short duration.

Calcium

The body's most abundant mineral. Its primary function is to help build and maintain bones and teeth. Calcium is also important to heart health, nerves, muscles and skin. Calcium helps control blood acid-alkaline balance, plays a role in cell division, muscle growth and iron utilization, activates certain enzymes, and helps transport nutrients through cell membranes. Calcium also forms a cellular cement called ground substance that helps hold cells and tissues together.

Serum

The cell-free fluid of the bloodstream. It appears in a test tube after the blood clots and is often used in expressions relating to the levels of certain compounds in the blood stream.

ng

Nanogram: 0.000000001 or a billionth of a gram.

Enzymes

Specific protein catalysts produced by the cells that are crucial in chemical reactions and in building up or synthesizing most compounds in the body. Each enzyme performs a specific function without itself being consumed. For example, the digestive enzyme amylase acts on carbohydrates in foods to break them down.

Asymptomatic

Not showing symptoms.

Cardiac

Pertaining to the heart, also, pertaining to the stomach area adjacent to the esophagus.

Hypertension

High blood pressure. Hypertension increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, and kidney failure because it adds to the workload of the heart, causing it to enlarge and, over time, to weaken; in addition, it may damage the walls of the arteries.

Carcinoma

Malignant growth of epithelial cells tending to infiltrate the surrounding tissue and giving rise to metastasis.

Melanin

A dark pigment produced in the skin. Dark-skinned individuals produce more melanin, and melanin production increases in response to sunlight, causing the skin to become darker.

Stroke

A sudden loss of brain function caused by a blockage or rupture of a blood vessel that supplies the brain, characterized by loss of muscular control, complete or partial loss of sensation or consciousness, dizziness, slurred speech, or other symptoms that vary with the extent and severity of the damage to the brain. The most common manifestation is some degree of paralysis, but small strokes may occur without symptoms. Usually caused by arteriosclerosis, it often results in brain damage.

Congestive

Pertaining to accumulation of blood or fluid within a vessel or organ.

Arrhythmia

A condition caused by variation in the regular rhythm of the heartbeat. Arrhythmias may cause serious conditions such as shock and congestive heart failure, or even death.

Pituitary

The pituitary gland is small and bean-shaped, located below the brain in the skull base very near the hypothalamus. Weighing less than one gram, the pituitary gland is often called the "master gland" since it controls the secretion of hormones by other endocrine glands.

Pancreatitis

Inflammation of the pancreas. Symptoms begin as those of acute pancreatitis: a gradual or sudden severe pain in the center part of the upper abdomen goes through to the back, perhaps becoming worse when eating and building to a persistent pain; nausea and vomiting; fever; jaundice (yellowing of the skin); shock; weight loss; symptoms of diabetes mellitus. Chronic pancreatitis occurs when the symptoms of acute pancreatitis continue to recur.

Insulin

A hormone secreted by the pancreas in response to elevated blood glucose levels. Insulin stimulates the liver, muscles, and fat cells to remove glucose from the blood for use or storage.

Gram

(gm): A metric unit of weight, there being approximately 28 grams in one ounce.

Cancer

Refers to the various types of malignant neoplasms that contain cells growing out of control and invading adjacent tissues, which may metastasize to distant tissues.

Hepatotoxic

Being toxic or destructive to the liver.

Hepatitis C

Caused by an RNA flavivirus. Transmission is predominantly through broken skin on contact with infected blood or blood products, especially through needle sharing. Sexual transmission is relatively rare. Symptoms are almost always present, and very similar to those for Hepatitis B: initially flu-like, with malaise, fatigue, muscle pain and chest pain on the right side. This is followed by jaundice (slight skin yellowing), anorexia, nausea, fatigue, pale stools, dark urine and tender liver enlargement, but usually no fever.